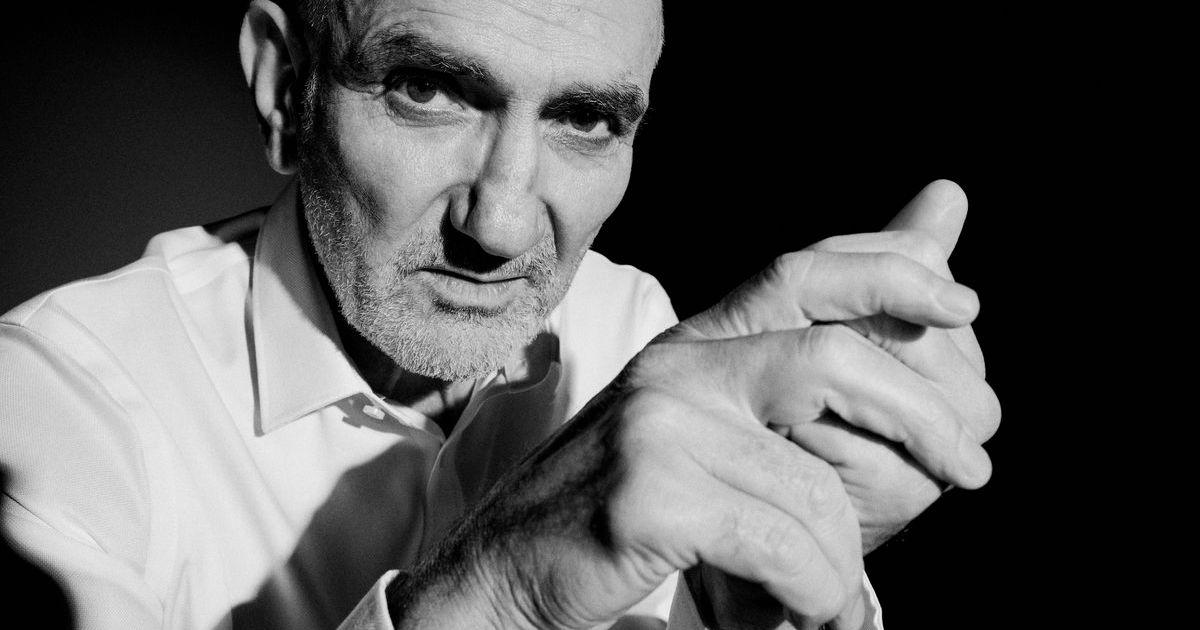

Billy Hughes: feisty fighter and maverick politician

Just say no: An anti-conscription rally in Melbourne in 1916 firmly rejected Prime Minister Billy Hughes's proposals. Photo: STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA

WILLIAM ‘Billy’ Morris Hughes was Australia’s longest serving politician, spending 58 years at a state, and then federal, level.

He was the Member for Bendigo between 1917 and 1922, and Prime Minister from 1915 to 1923.

A political maverick, he began his career with the Labor Party in NSW in 1894 and ended it as a Liberal MP, dying in office in 1952 at the age of 90.

In the intervening years he was a fierce trade unionist, lawyer, and a member of almost every Australian political party except the Country Party.

But his pro-conscription stance in World War One was to divide the nation.

The defence act of 1910 allowed for compulsory military service within Australia, but not overseas.

Hughes, a British-born patriot, wanted to maintain Australia’s commitment to support the allied war effort.

He was of the opinion that voluntary enlistment levels were not high enough to meet the number of soldiers needed to fight an escalating war in France.

On the first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, out of 57,000 casualties, more than 19,000 died, making it the bloodiest day in British military history.

This level of carnage made many Australians uncertain about what had previously been an unquestioned level of support for the British Empire.

Hughes had become Prime Minister after Andrew Fisher resigned in October 1915.

His moves to increase Commonwealth powers in a number of areas had already seen him go head-to-head against many of his fellow Labor Party MPs.

The 1916 conscription plebiscite was the last straw and the party expelled him after a narrow win for the ‘no’ position in late October.

Hughes subsequently joined forces with the opposition and called an election in May 1917.

His new Nationalist party won a resounding victory with 53 seats to Labor’s 22, while Hughes abandoned his previous Sydney seat for Bendigo.

Popularly known as the ‘little digger’, Hughes had cemented his position as a wartime leader.

McIvor Times proprietors Edward Johnson and David Dobbin were strong anti-conscriptionists and they were unwavering in their contempt of Hughes and his views.

While Heathcote itself was then part of the Echuca electorate, a nearby MP who also happened to be Prime Minister commanded many column inches.

On the eve of the first conscription plebiscite in October 1916, Johnson and Dobbins penned an article that showed exactly where their allegiance lay.

Under the heading ‘Think before you vote’, they said conscription would “damn the heritage of this free Australia.

“For time immortal we, and the generations that follow, us will be bound in the shackles of militarism.”

By April 2017, and with an election on the horizon, they were to describe a policy speech given by Hughes in Bendigo as “the customary tirade of abusive (sic) against the old friends from whom he has broken away” full of “long-winded phraseology wrapped around an inconsiderable quantity of facts”.

Johnson and Dobbin wrote that supporters of the newly formed Nationalist coalition, led by Hughes, were making “rambling, reckless and often ridiculous statements”.

They also claimed that the failed conscription plebiscite had cost an estimated £500,000. “If one twentieth of this colossal sum had been put into a voluntary recruiting campaign the result would have been different, and all the scandals and fuss of an early election avoided,” they wrote.

“Hughes is at the bottom of every mistake.

“He has led three Governments in a few months, and has brought disaster upon them all.”

However, the landslide success of the Nationalists emboldened Hughes to launch another public vote on conscription in December 1917.

The no vote again triumphed, but the war was drawing to an end and Hughes was now focusing his energies on representing Australia in the peace process.

When asked by US President Woodrow Wilson about his right to take part in these discussions, given Australia’s small population, Hughes reportedly replied, “I speak for sixty thousand dead. For how many do you speak?”

Physically small in stature, hard of hearing, notoriously cantankerous and mercurial, Billy Hughes managed to cast a long shadow over Australian politics for more than five decades.

After his death in 1952, then Prime Minister Robert Menzies paid tribute.

“I find it very difficult to believe that this is the first day in the history of this parliament that William Morris Hughes has not sat as a member,” Mr Menzies said.

“It is the first day after half a century.

“He was one of the original members of the first Commonwealth Parliament remaining in this house or in this parliament.

“His I think, was, of all the lives that we have witnessed in Australia, the most astonishing.

“A little man, a wisp of a man, must have tremendous personality to assert himself over vast multitudes of people and he did.”