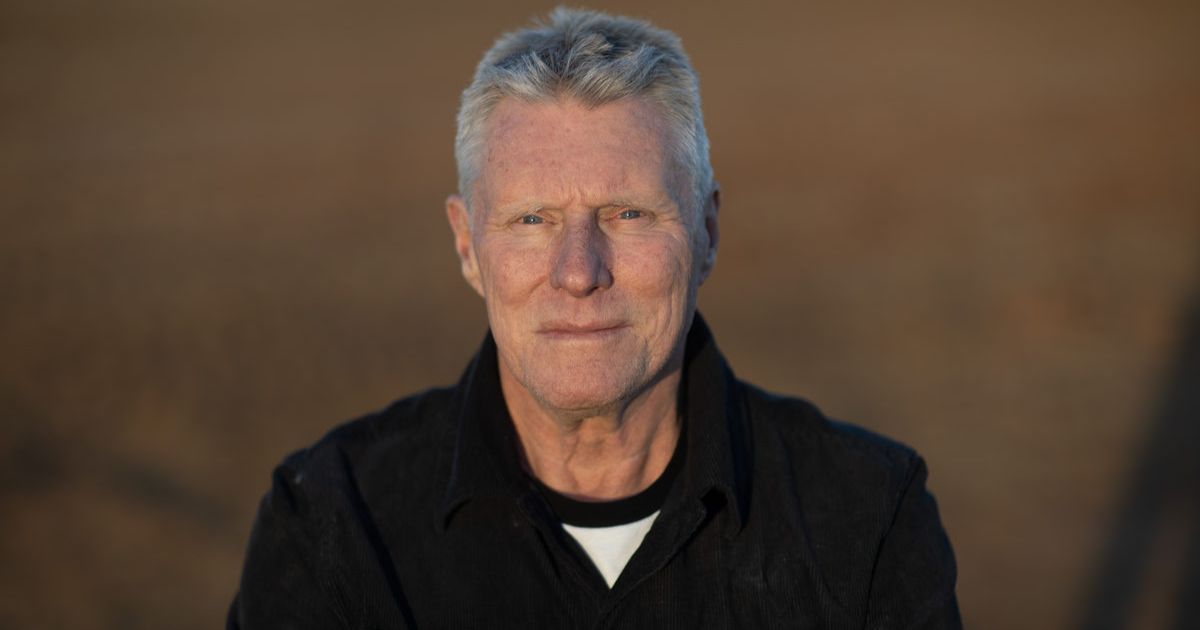

Barry Jones in conversation with Kerry O’Brien

AT the Byron Writers Festival, veteran journalist Kerry O’Brien joined author and former science minister Barry Jones on stage for a rare and wide-ranging conversation.

O’Brien, with that unmistakable voice and authority that defined decades of interviews, was there to guide Jones through the labyrinth of his own mind.

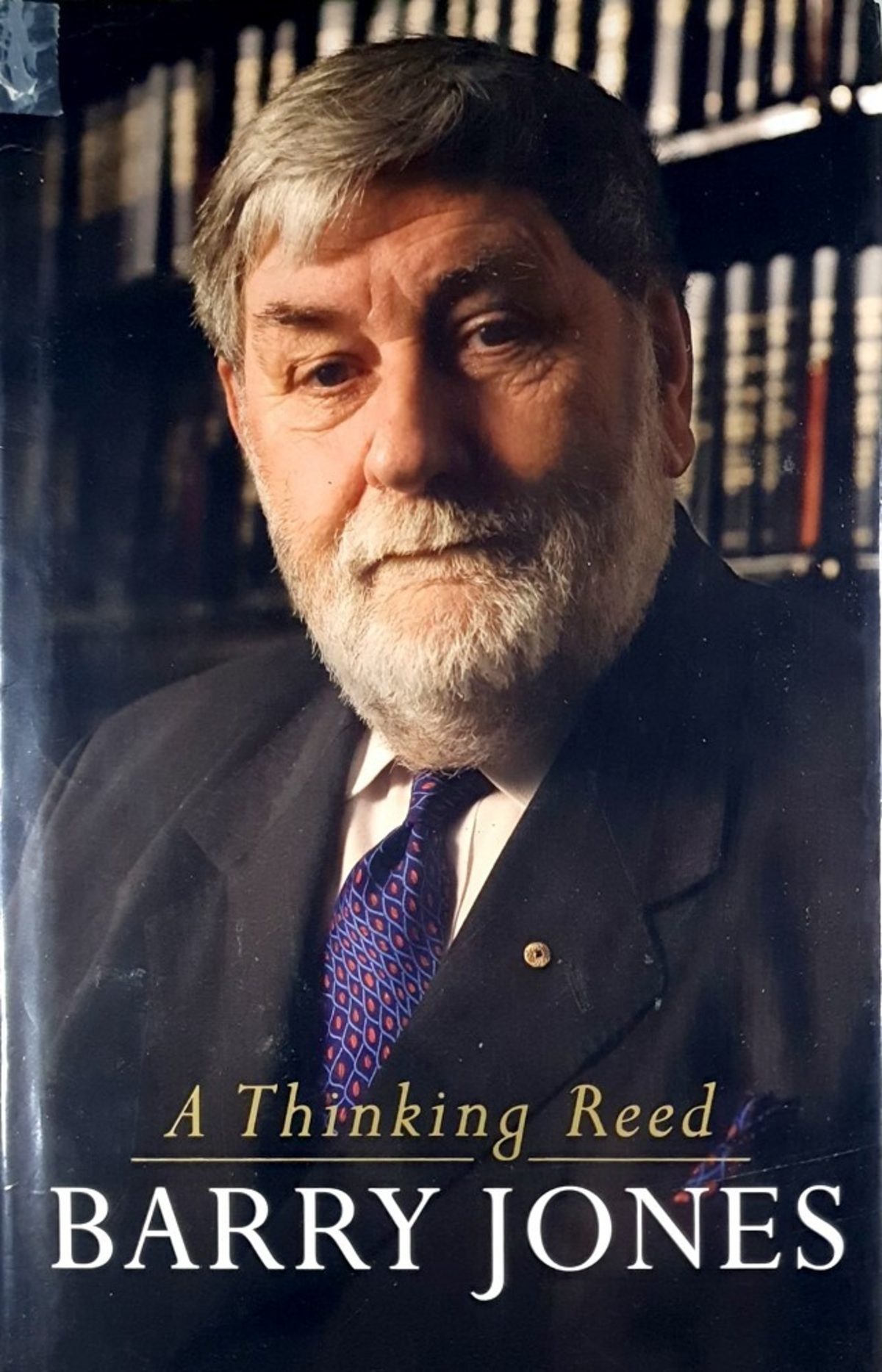

Jones’s career has taken him from the classroom and the early days of Australian talkback radio to a seat in the Victorian parliament in the 1970s and then the federal arena from 1977.

In Canberra he held portfolios including science, small business, consumer affairs, and customs. He was known for championing biotechnology and climate policy long before they became political priorities.

Away from parliament, he helped revive the Australian film industry, served on the executive board of UNESCO, presided over the Labor Party nationally through the 1990s, and represented Australia on the World Heritage Committee.

His books, including the international bestseller Sleepers, Wake! and the Dictionary of World Biography, have cemented his place as one of the country’s most recognisable public intellectuals.

Before a packed hall, O’Brien began by reading from Blaise Pascal, the 17th-century French philosopher who described man as a “thinking reed” fragile yet capable of thought that can grasp the universe.

It was a fitting image for Jones and the title of his 2006 autobiography.

Jones said that life wasn’t just about thinking well but also acting well.

“It’s useless if you just have a great smile of satisfaction and say, ‘Well, I’ve read that, it’s a pity.'”

“The point is you’ve got to get up and engage. You’ve got to be engaged. You’ve got to be involved in the whole process.”

Jones said that as revolting as the political process almost always is, unless you become involved and are prepared to lose some skin, lose some friends and perhaps some money as well, nothing will change.

“If you want the greatest objective of all, which is to save the planet and save civilisation and save the quality of life and save nature as we understand it, you’ve got to be prepared to put your bum in it.

“You can’t just sit back and say, ‘Well, somebody else can do it.’ You all have a personal responsibility.”

O’Brien described Jones as someone whose mind never stopped processing, drawing unexpected links between science, art, politics and history.

He took the audience on long, discursive journeys that looped through his life and ideas, sometimes doubling back, sometimes disappearing into side streets before returning to the main road.

“If I knew I was going to die next week, but there was a performance of The Marriage of Figaro tonight, would I go? You bet!” Jones said.

“Because every time you see a great work like that, a real masterpiece, you understand somehow something about the whole cosmos.”

The conversation ranged across his career.

He warned about the decline of manufacturing jobs in the early 1980s and campaigned for a price on carbon decades before it became law.

Often, he said, he felt like a prophet without honour in cabinet.

“Some of these things I was talking about in the 1980s, we are now right up against the wall on,” he said, his voice dropping. “We are very close to the point of no return.”

O’Brien moved the discussion to authoritarianism.

Jones drew connections between Donald Trump’s rise and 1920s and 1930s European fascism, noting how grievance politics and institutional decay can hollow out democracies.

When asked about the Gaza war, Jones paused, then began speaking about the shortness of time for himself and for the planet.

“Time is running out for me personally, but time is also running out for the planet,” he said, before moving into familiar terrain.

He spoke about climate change, the need for urgent action on global crises and the interconnectedness of human survival.

O’Brien let him go on uninterrupted, then tried again, suggesting he might have misheard and offering another chance to respond.

Jones again folded the question into his larger argument about the fragility of civilisation.

To him, perhaps Gaza may not have been only a geopolitical crisis but a symptom of something larger.

A more direct answer never came.

Jones also spoke about faith and mortality. He described himself as a “northern hemisphere Christian” because most of his transcendent moments have been in European cathedrals.

O’Brien noted that Jones had addressed the subject three years earlier at the inaugural Sorrento Writers Festival.

He read from that speech:

“Like most people, other than fundamentalists, I feel shifty and inconclusive on the subject, because of a deep uncertainty about what I believe.

“That the universe is mysterious? Yes. That God exists? Possibly. That Jesus was a uniquely powerful and charismatic teacher? Yes. That he had a special or even unique relationship with God? Unanswerable. That the Church is a divine institution? No. That the Bible is infallible? No. That there is a soul, linked to a collective consciousness? Remotely possible. That there is life, as we know it, after death? Unlikely.”

O’Brien looked up.

“So, where does that leave you now in terms of belief?”

“I think that’s essentially where I am,” Jones replied.

The hour closed with a return to the Pascal image.

The thinking reed was still bending, still reaching to make sense of a chaotic world, still warning about the dangers ahead.

“We cannot afford complacency,” Jones said. “We must be prepared to think, to act, to face reality.”

O’Brien’s steady hand throughout, drawing him back when needed and letting him roam when the stories and ideas flowed, gave the conversation shape without cutting off its vitality.

For those in the hall, it was a reminder that Australian public life once had space for figures like Barry Jones: erudite, unpredictable, sometimes maddening, but always thinking.

His most recent book, What Is to Be Done (2020), continues that lifelong engagement with the big questions.