Exploring LCH to better patient outcomes

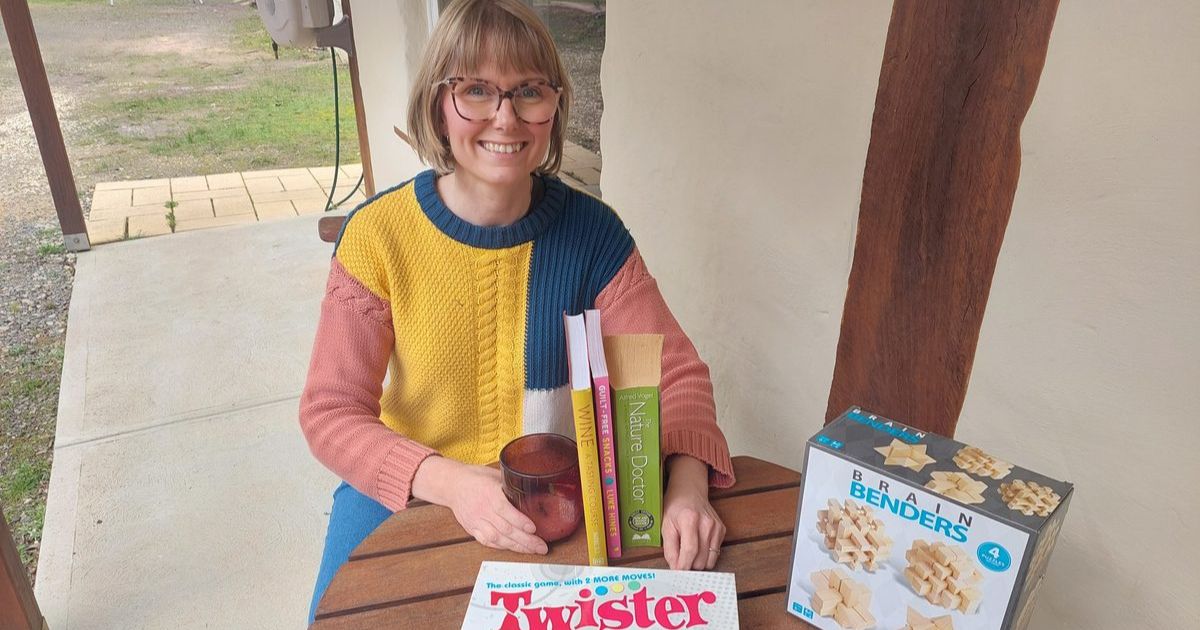

Making discoveries: Dr Jenee Mitchell has been with FECRI for a decade, and explored abnormalities in T cell lineages in patients with LCH during her PHD. Photo: EDWINA WILLIAMS

RECENT Fiona Elsey Cancer Research Institute investigations have looked at the immune systems of people with Langerhans cell histiocytosis to better understand the disease and improve patient outcomes.

Dr Jenee Mitchell and Professor George Kannourakis have led the research into LCH, a rare disease occurring most commonly in children, where lesions grow, and can infiltrate and damage organs throughout the body.

It occurs in one in 200,000 children under 15 years of age per year, but it can be difficult to diagnose, so may be much more common than researchers realise.

“These lesions consist of LCH cells, and they’re thought to be the ‘bad cells,’ that express a molecule on their surface called CD1a,” Dr Mitchell said.

“Given the expression of this molecule, we think this might play a key role in disease progression.

“There’s a type of white blood cell or immune cell called T cells, and there’s a group of these T cells that can recognise the CD1a molecule on the surface of the LCH cells.

“These cells are thought to have a role in skin immunity. They’re not well studied because the reagents that are used to detect this subset of T cells have only recently become available but what we know is that they might play a role in a lot of different diseases including cancer and autoimmunity.”

Dr Mitchell said it’s “surprising” no other researchers have focused on these cells in LCH given the CD1a expression, and recognition from T cells.

But, with Professor Kannourakis and the resources of FECRI, she’s doing her bit to advance this scientific area now, and has published an article about it.

“We’ve reviewed what’s currently known about expression of CD1a molecule in LCH and we’ve highlighted that there’s a potential role for these T cells that recognise CD1a in the progression of LCH,” Dr Mitchell said.

“Our findings from this article build on our current understanding of LCH the disease and can lead to improvements in patients’ overall wellbeing.”

This is important as the current treatment for LCH is the same as it was approximately 60 years ago, and it’s not successful in every case.

“For some people, the prognosis and outcomes are pretty good, but for about half of all patients that are treated with the standard treatment they have a recurrence, so we really need to improve the treatment options,” she said.

“Because we’re looking into the immune system, treatments are also potentially transferrable across a lot of different diseases such as cancer and autoimmunity.”

Dr Mitchell’s PhD explored abnormalities in T cell lineages in patients with LCH, and she has been studying the disease in the lab at FECRI for nearly 10 years.

Her day-to-day work has included looking at live cells through a flow cytometer, staining cells with fluorescent antibodies, and plenty of data analysis.

Research into T cells continues at the Institute, with an aim to establish a deep characterisation of the tissue environment through digital spatial profiling.