From the desk of Roland Rocchiccioli – 25 April

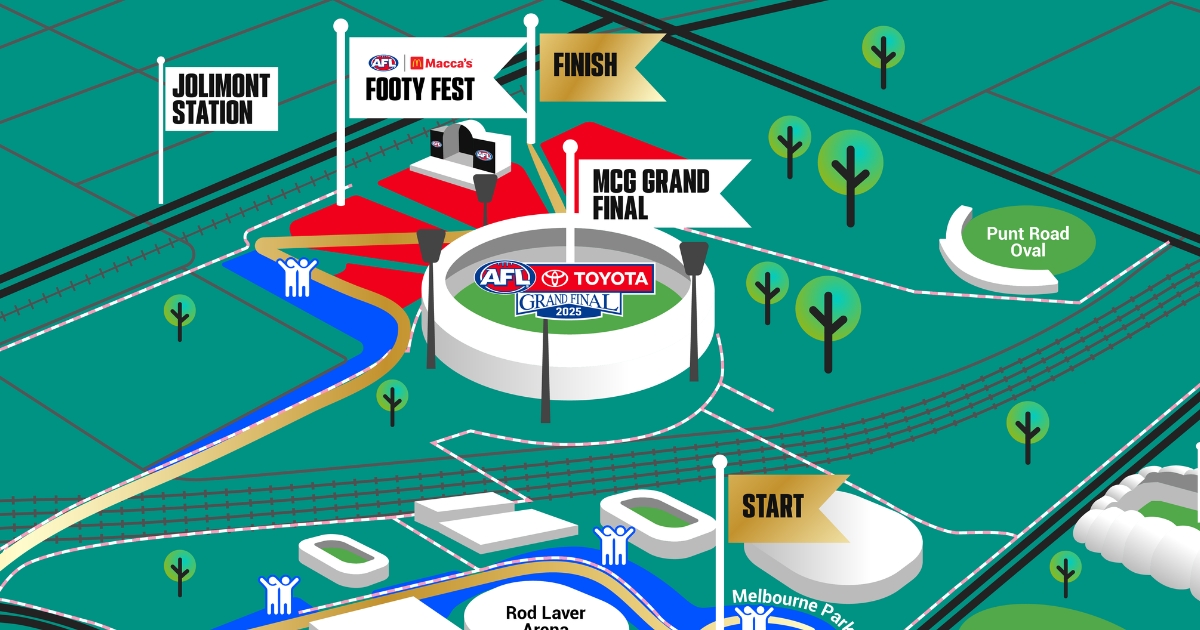

Lasting monument: The battle of Fromelles, 19 July 1916, was a bloody initiation for Australian soldiers to warfare on the Western Front. Photo: SUPPLIED

War is not the opposite of peace; it is the break-down of society. The most powerful warriors are time and patience.

AT exactly this time, 101-years ago, the thousands of young men who left Australia as boys, to fight for King and Country – and to be part of the ‘big boys’ adventure on the other side of the world, and in countries they were hard-pressed to find on the classroom globe – were returning home from the Great War. Joyfully, they left their wide-brown land and its endless blue skies with a smile and a swagger; their Slouch Hats at a jaunty angle. They returned in a more sombre mood. They saw and experienced horrors they never imagined. The abiding memories of the blood and the mud of trenches would haunt them, silently, for the rest of their days. They tried to pick-up the threads of their shattered lives. They struggled valiantly, but for many it was unbearable. The shellshock blighted their every living moment, day and night. For a number, death by suicide was preferable to the consuming pain and crippling anguish.

They said, when the hostilities broke-out in the July/August of 1914: “It’ll be over by Christmas!” They called it the War to end all Wars. Devastatingly, it lasted four-years (1914-18) – and was one of the deadliest conflicts in the history of the human race. The total number of both civilian and military casualties is estimated at around 37-million people. It is impossible to establish an exact figure. Around 2-million people died from war-related diseases; a further six-million went missing, presumed dead. Two out-of-three soldiers died in battle; the rest from infections or disease. Also, Spanish flu claimed hundreds held in prisoner-of-war camps.

War correspondents sent back graphic eye-accounts of German atrocities which left readers reeling in despair.

On August 25, 1914, the German army ravaged the Belgian city of Leuven. They deliberately burned the university’s library of 300,000 medieval books and manuscripts which shocked the world and brought international condemnation. The Daily Chronicle described it as war not only against civilians, but war against “posterity to the utmost generation.”

The rampaging German soldiers killed two-hundred and forty-eight residents, and expelled the entire population of ten-thousand. Civilian homes were set on fire; often citizens where shot they stood. Over two-thousand buildings were destroyed, and strategic materials, foodstuffs, and modern industrial equipment were looted and transferred to Germany. In the confusion there were several incidents of Germans shooting and killing their own men. In the Belgian Province of Brabant, Flanders, nuns were ordered by Germans to strip naked under the pretext they were spies. In Aarschot, between August and September, women were repeatedly victimised. Looting, murder, and rape was widespread.

With the end, 11 November 1918, came an enduring legacy of sorrow, on both sides of the conflict. Thousands of families were left with only the memories of husbands, fathers, sons and daughters. Many grieving widows never married again. Around the world, war-damaged veterans – the wounded, the limbless, the burned, the gassed, and the blind – were a visible, living reminder of man’s brutality to man. They said this must never happen again! In a spirit of reconciliation, Ataturk, and his Turkish people, held-out the hand of compassion and embraced the souls of our dead soldiers at Gallipoli, “Those heroes who shed their blood and lost their lives, you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side in this country of ours. You, the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears, your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they become our sons as well.”

Roland can be contacted via [email protected] and you can hear him every Monday morning – 10.30 – on radio 3BA.