Lost Heathcote

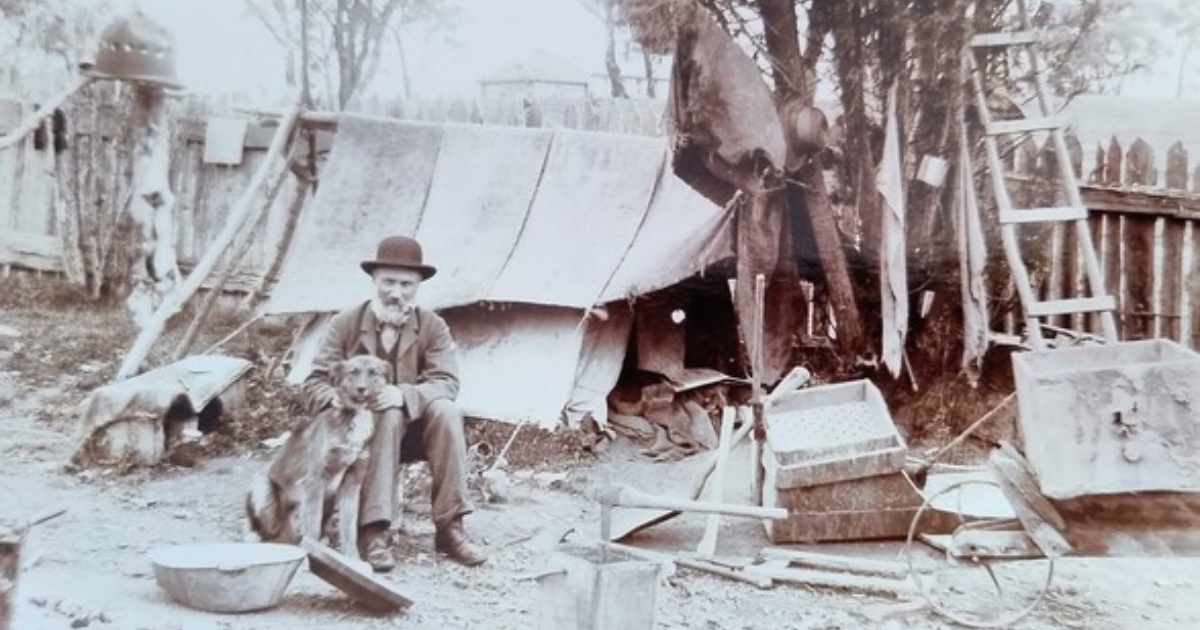

Simple living: Gold miner Reginald Shaw at his camp in 1898. Photos: R GATES/HEATHCOTE MCIVOR HISTORICAL SOCIETY

WHEN Heathcote bank manager Roderick Gates ventured out with his camera in the 1890s, he captured the last remnants of a bygone era.

The lively tent towns of the early McIvor diggings were only a memory, however there were still people living locally under canvas or in small wooden huts.

Gold miner Reginald Shaw was snapped at his camp in 1898, dressed in what appears to be his Sunday best.

But the suit and tie were in sharp contrast to his primitive makeshift tent with its hessian overlay and the mining implements scattered on the ground.

Gates also photographed two women outside a tent in the bush, and an older couple on the veranda of their ivy-clad cottage.

All three images portray a very basic lifestyle with tiny inside spaces for living and sleeping, and no running water or any form of modern plumbing.

In 1894, Yarrawonga resident Gordon Duncan recalled his early days on the McIvor goldfields in an article for the McIvor Times.

“What changes, how different the surroundings,” he wrote.

“Then McIvor was all bustle, animation and business with an adult male population numbering tens of thousands, busy as ants by day, with abodes of calico to retire to for their hard-earned rest at night.

“Today, Heathcote a well-built, pretty little town has only one street, one, however, of which its inhabitants are justly proud, for it certainly is a majestic thoroughfare several miles in length, with trees on both sides of the road, forming a delightful shade to pedestrians on the footways and a noble avenue along the roadway.

“The greatest contrasts noticeable to me were: first, that the newly turned soil of by-gone days has given place to a carpet-like surface of green sward, especially noticeable on the Commissioner’s Flat.

“Secondly, the lack of animation in the town, utter dullness seems to pervade the place where 40 years ago everybody was as busy as bees hiveing.”

But this perceived dullness also came with much greater security and comfort.

There were several early accounts of tents being carpeted for warmth, but they were still very susceptible to local wildlife and the weather.

In April 1866, the McIvor Times reported on a miner’s close encounter while making his bed.

“A large whip snake glided from between the blankets and escaped into the bushes behind the tent,” it said.

The reptile was caught the next day and it “measured nearly five feet.”

In April 1869, the paper described the tribulations of families at the Spring Creek diggings between Heathcote and Rushworth.

They were living in “badly pitched tents, half-furnished buildings, huts composed of bark curled up like sticks of cinnamon and neither wind-tight nor water tight, in which the inmates could study astronomy and take observations through the roof in fine weather,” it reported.

“Numbers of people have discovered that they have rather over done the thing in the way of that highly necessary precaution, the ventilation of their dwellings.”

Earlier, in September 1863, the McIvor Times highlighted a common problem that was to plague tent dwellers for decades.

“This district is at present infested with some of the lowest class of thieves,” the editor wrote.

“Tent robberies are of very frequent occurrence; the petty marauders appear to consider anything fair plunder, from a lump of beef, the contents of a digger’s sugar bag, or a stale loaf to a watch.”

And while fewer people were living in tents by the 1890s, burglary was still an issue.

In July 1895 the paper reported that items “were disappearing for some days previous from the hut and tents of miners at Mitchellstown workings, one man losing his billy, blankets and provisions.”

Most miners lived under harsh conditions until they either struck it rich, or abandoned their quest and took up more regular employment.

While there are many reminders of the gold rush era in the Heathcote district, including more substantial miner’s cottages, the flimsy temporary structures are long gone.

Few images of these remain and the Gates Collection of photographs is a small, but valuable, record of a vanished world.