For whom the brand tolls

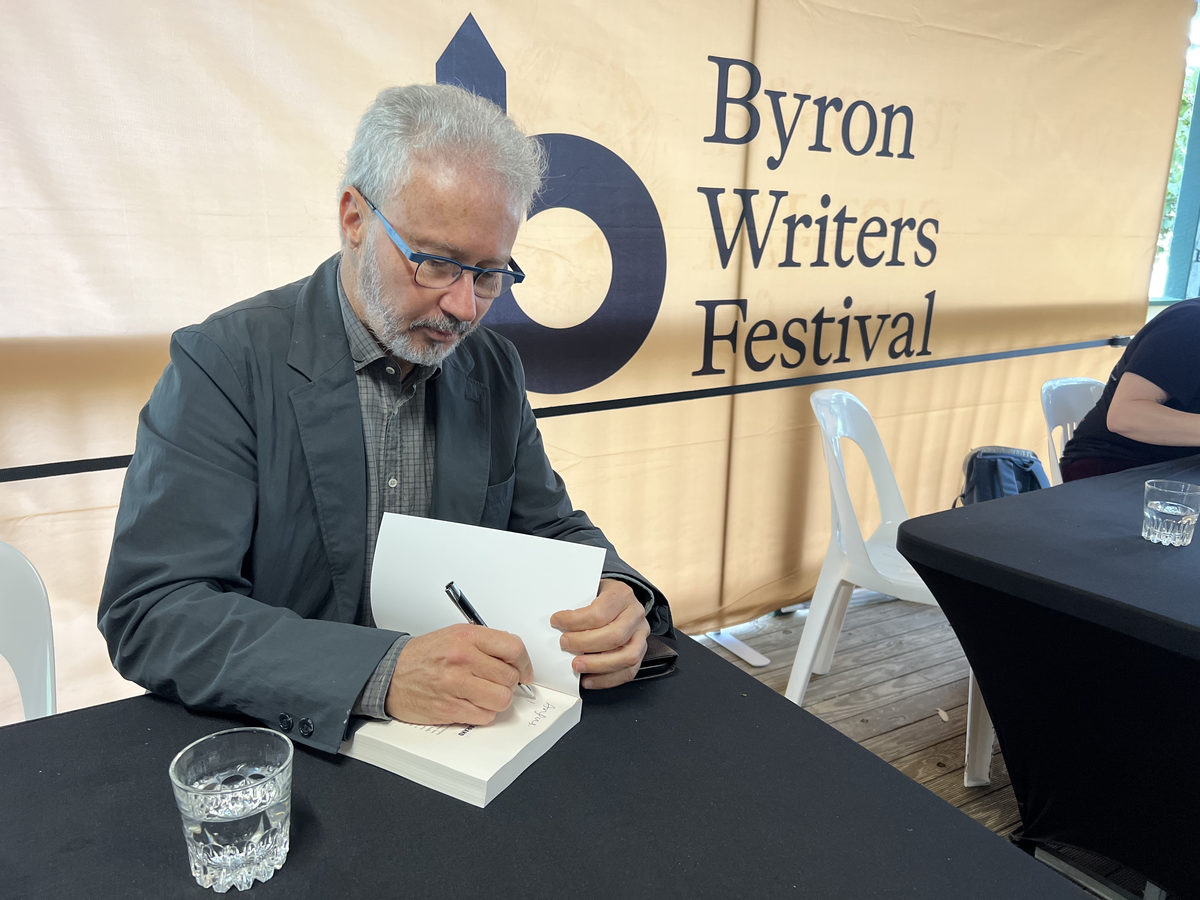

From universities to airlines to the ABC, Josh Bornstein sees a common thread: corporate power shaping the boundaries of public speech. In conversation with Julianne Schultz at Byron Writers Festival, he explained why this creeping control should worry anyone who values democracy.

AT the University of Sydney, you cannot fly a flag from your office window without permission from the “brand team.”

When Julianne Schultz tells an audience this, a ripple of nervous laughter moves through the marquee. The staff member in question put up a Palestinian flag and was told to take it down.

Bornstein wasn’t surprised. According to him, that’s what brand management looks like in 2025.

“Corporations started undermining the tax system by avoiding taxation, smashing the environment and sabotaging attempts to mitigate climate change, smashing unions, suppressing wages, redistributing wealth, as their behaviour deteriorated,” he said.

“As they sacked people and outsourced them to Bangladesh, they invested more heavily in brand.

“Why? To maintain their legitimacy and their enormous political power. And it’s been pretty successful.”

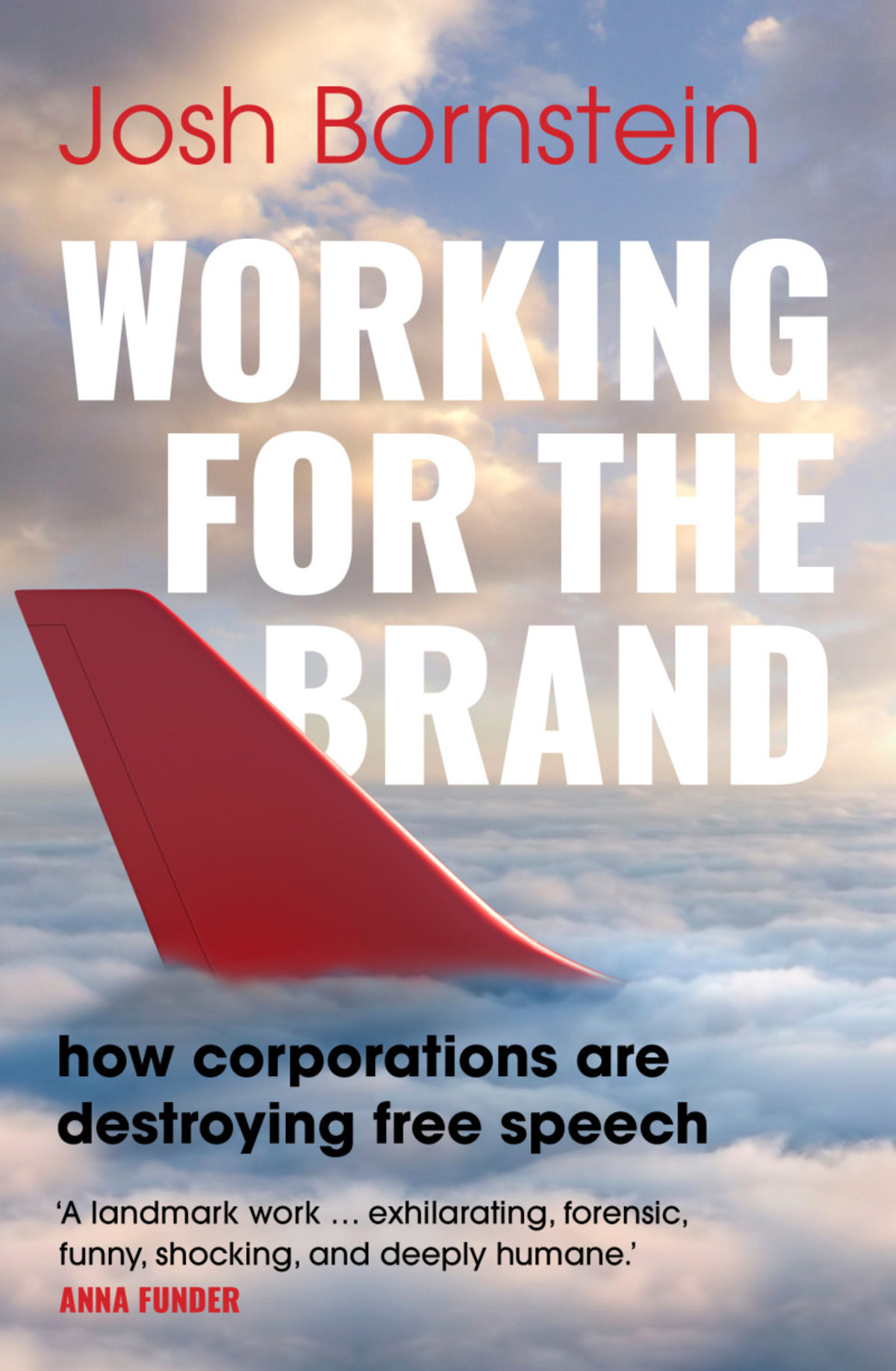

Bornstein said there is a study he refers to in his new book Working for the Brand that shows a brand which positions itself as ethical survives scandals about its inevitable unethical behaviour.

“So, brands like Nike or Apple which have been exposed to using child labour and other abuses and undermining taxes and so on seem to be pretty impervious to any damage, in part because they’ve got ethical brands,” he said.

“So my theory is that in order to shore up their position and to mask bad behaviour, companies very intensely went into brand management. It’s a dark art.

“And as corporations and corporate conduct and market values became more and more prevalent, they’ve been adopted by universities so we get that sentence, that jarring sentence, that whether a Palestinian flag flies at a university is to be discussed with the brand management team.

“Universities have become incredibly corporatised, as we all know, and they now implement the same brand management and brand strategies that we’ll see ExxonMobil does or BHP.”

One of Australia’s most prominent workplace lawyers, Bornstein has spent decades fighting for workers and whistleblowers, often against the country’s largest corporations. In Working for the Brand, he argues these companies have quietly become “private governments,” exercising a level of control over employees that no democratic government could get away with.

The rules are often buried in contracts that demand brand loyalty at all times, in all places, on and off the clock.

“It is an incredibly repressive, anti-democratic bargain,” he said.

Bornstein began noticing the shift years ago as contracts grew longer, clauses more restrictive, hours stretched, and permanent jobs were reclassified into insecure arrangements. Private speech became a workplace issue. Even a silent presence at a protest could be grounds for discipline.

Qantas under former CEO Alan Joyce provides one example. The airline was celebrated for taking progressive stands while cutting jobs, avoiding tax and reducing service.

“They were very active in the same-sex marriage campaign and other causes,” he said.

“Meanwhile, they turned a premium airline into something closer to a budget carrier charging premium fares.”

The approach worked. Even with its brand reputation battered, Qantas continued to post record profits, protected by its monopoly position.

In the public sector, one of the clearest examples for him is the ABC. He represented journalist Antoinette Lattouf after she was suspended for posting that Human Rights Watch had reported starvation was being used as a weapon of war in Gaza, a statement now widely accepted as fact.

The ABC, he said, fought the case like a corporation intent on silencing a whistleblower. It rejected settlement offers, racked up more than $2 million in legal bills and was ultimately humiliated in court when its evidence was discredited.

His first direct encounter with what he calls “corporate cancel culture” came almost a decade earlier, with the case of SBS journalist Scott McIntyre. The backlash was swift after McIntyre posted tweets critical of Anzac Day.

He and his family received death threats, and his wife fled to Japan with their children. Under Japan’s custody laws, he has not seen them since.

When Bornstein spoke to him for the book, McIntyre was couch-surfing and campaigning for legal reform, his career and family life in ruins.

Cancel culture, Bornstein said, has gone from bad to worse and is at times backed by political leaders, major media platforms and, in extreme cases, the threat of violence. In some cases, the risks go beyond careers.

He cites Anthony Fauci, who required round-the-clock security during the pandemic, and his own experience of being targeted by a 22-year-old extremist.

The man impersonated him, published fabricated articles in the Times of Israel under his name and spread them globally. One called for the elimination of Palestinians. Death threats arrived from around the world.

The attacker set up fake social media accounts, paid for tweets calling for the death of Muslims and tried to incite ISIS to target Bornstein.

“At some point I stopped coping,” he said. “I lost weight, stopped eating, lied to my wife and my children because I thought that was the lesser of the two evils.”

Months passed before a law student and an Australian journalist uncovered the perpetrator’s identity. The AFP and FBI arrested him in Florida while he was preparing to bomb a 9/11 memorial. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The trauma, Bornstein said, still lingers.

Working for the Brand is out now through Scribe Publications.