Grit, hats and heritage

THE story of Akubra’s newest store in Byron Bay began a long way from the coast.

In 1876, English-born hat maker Benjamin Dunkerley set up shop in Tasmania and began refining a way to turn rabbit fur into felt.

It was hard, dirty work, but his invention changed Australian hat-making and gave rise to a name that would outlast wars, droughts and fashion fads.

Nearly 150 years later, each hat still passes through more than 60 pairs of hands. It remains a company defined by craft, stubbornness and pride.

Peter Fowler, Akubra’s chief commercial officer, says that kind of endurance is rare.

“Akubra is the people’s brand,” he said.

“It lives in storytelling more than any other brand I’ve worked with. Everyone has a story about their Akubra.”

For many Australians, that story begins on a trip, a farm, or under the hot Aussie sun somewhere in the dust.

Fowler says that’s what drew him to Akubra, not just the craft but the people who live in the hats and make them part of their story.

“It becomes about the people who wear it rather than the product itself,” he said. “That was super appealing.”

Every hat, he said, carries a story of work, travel and place, and that connection between people and product is what keeps the brand alive.

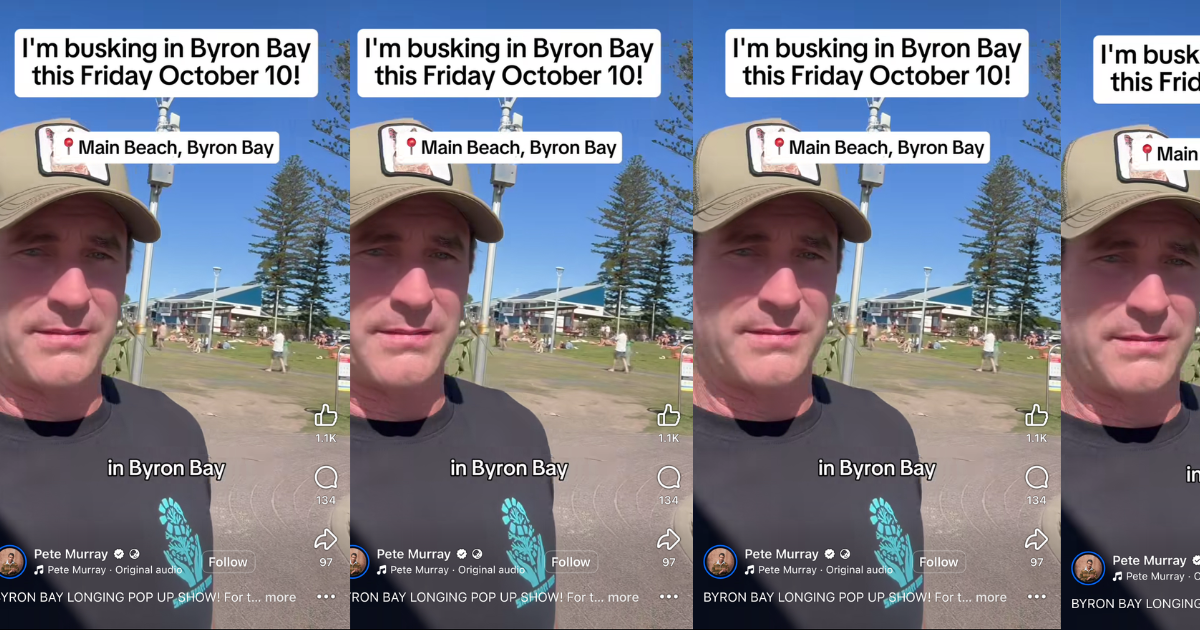

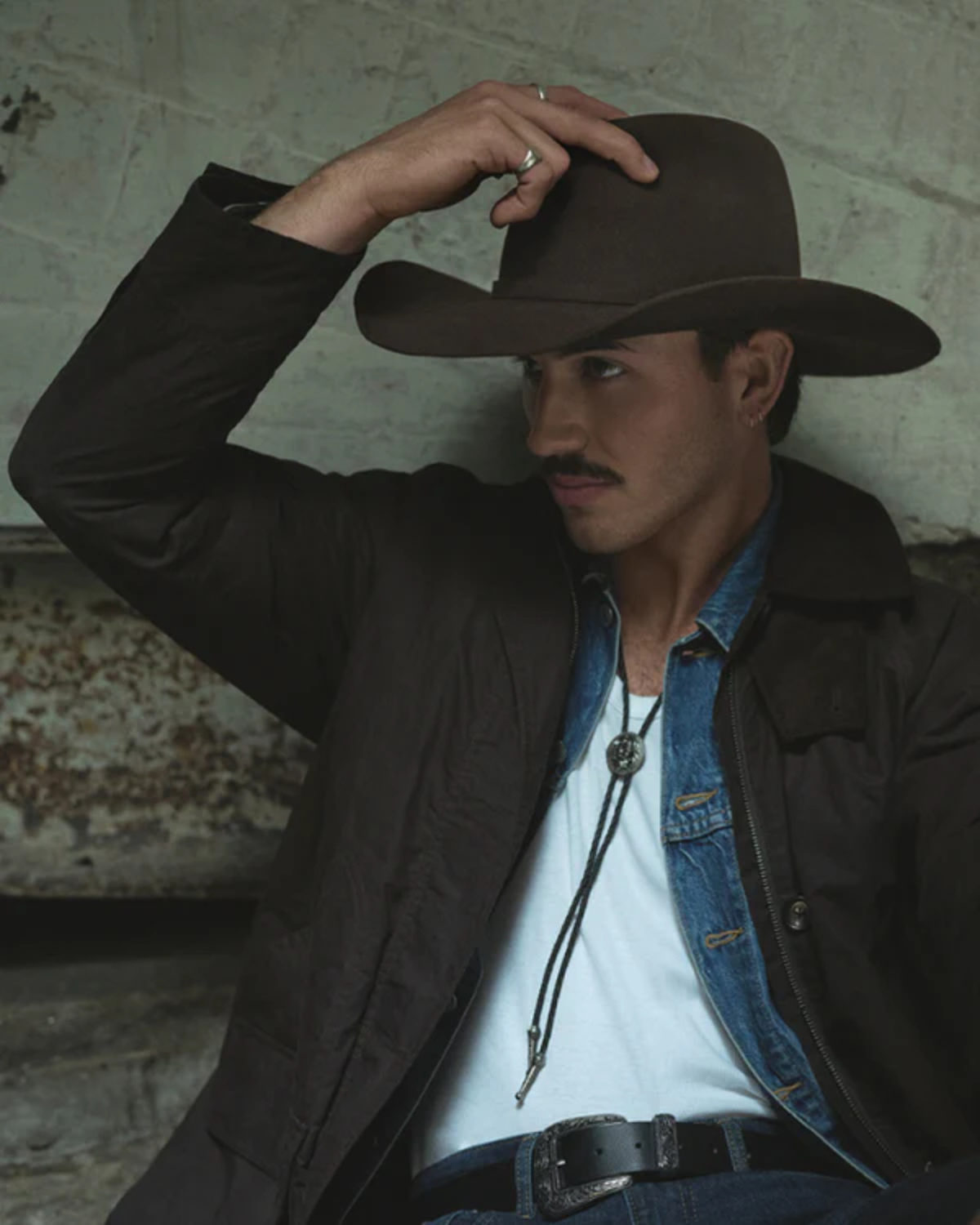

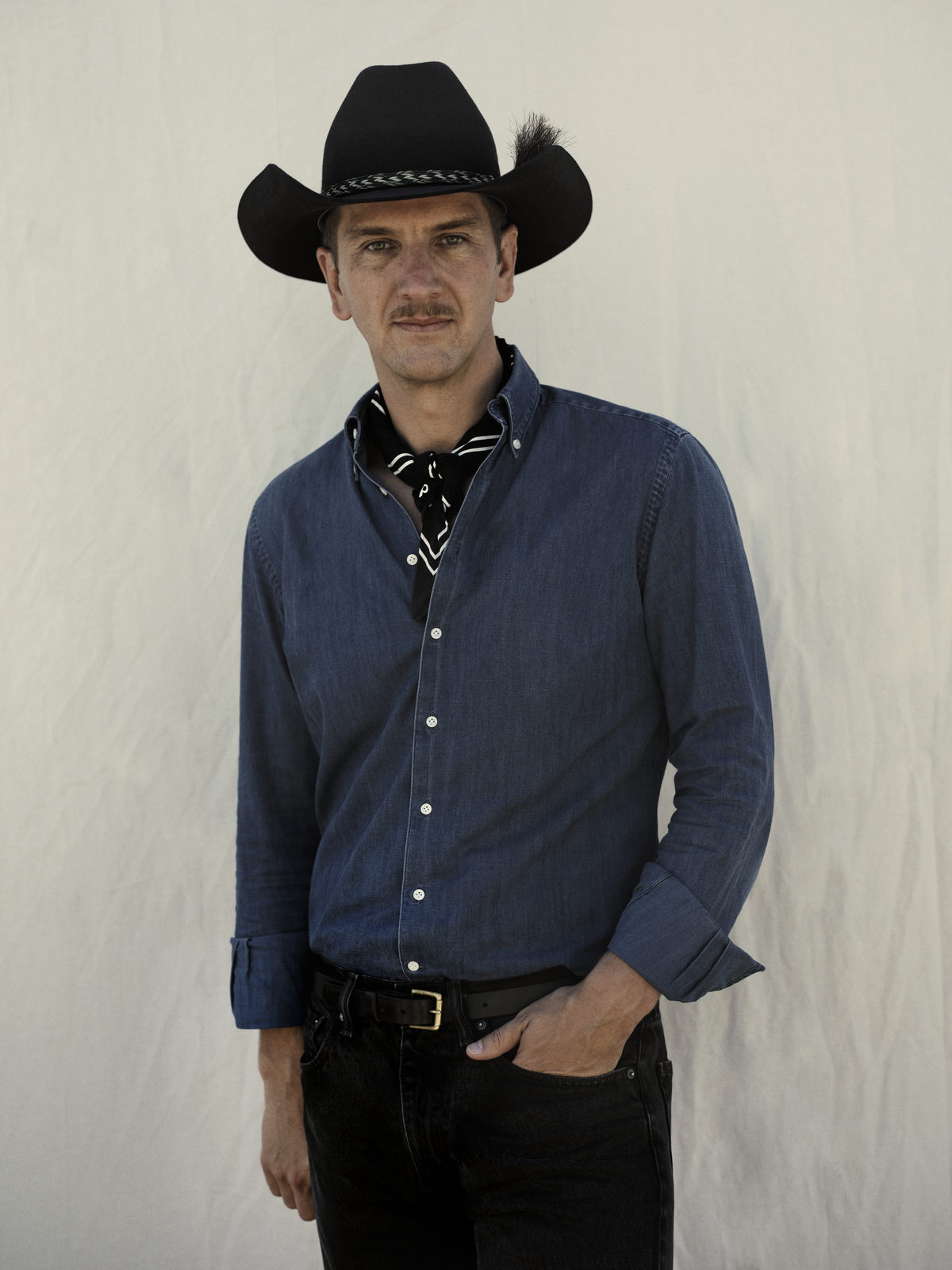

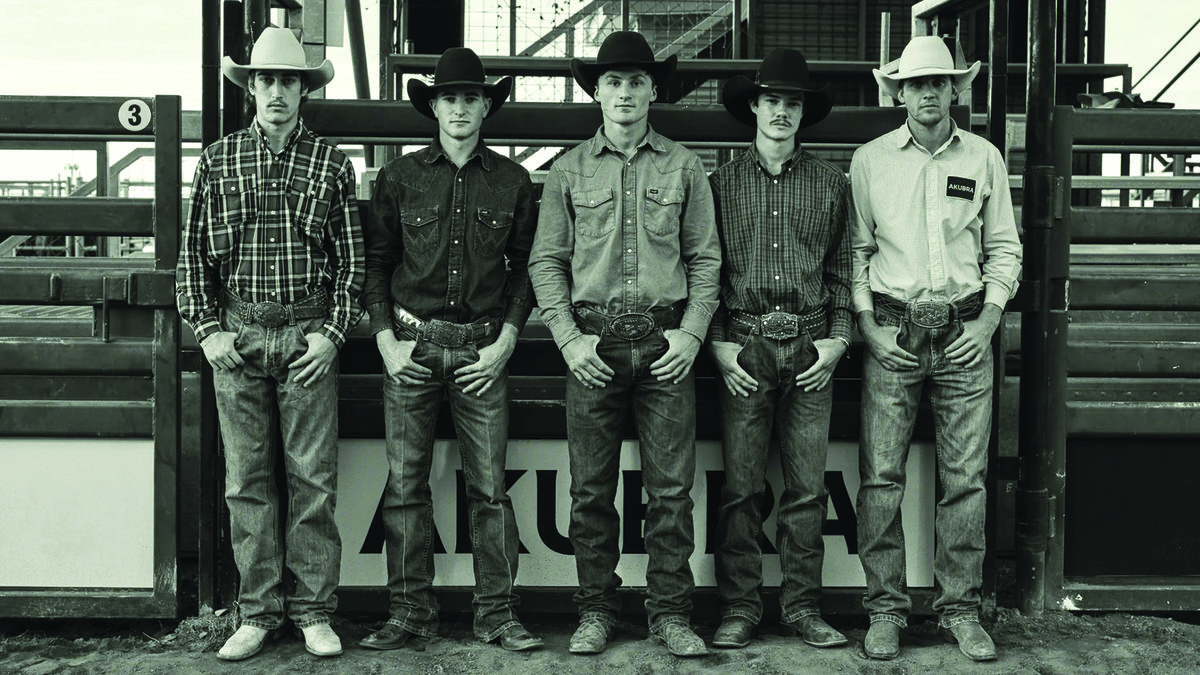

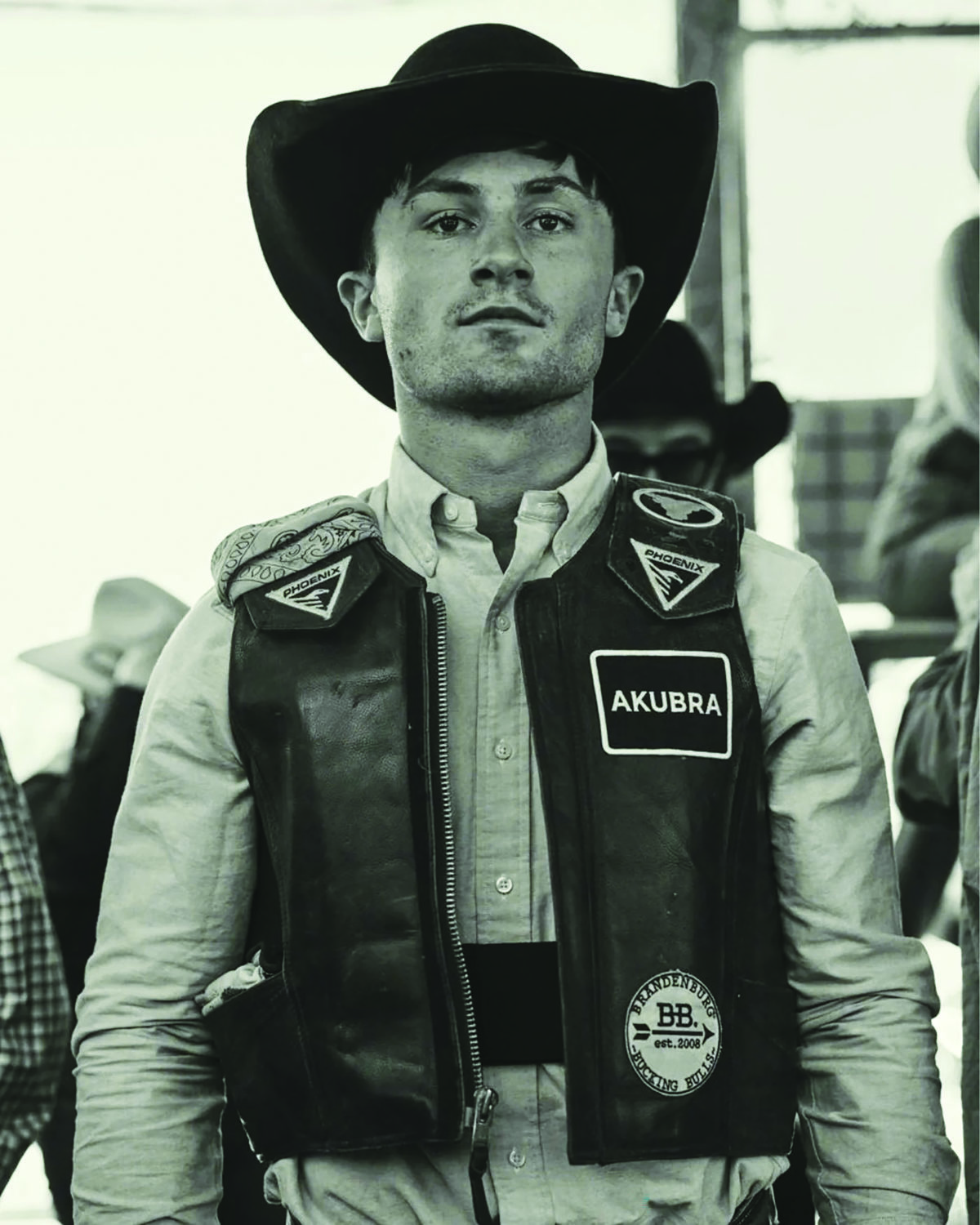

Today, Akubra’s story is told by many hands and faces, from stockmen and rodeo riders to photographers, musicians and city dwellers who carry the hat’s spirit in their own way.

That mix of people, Fowler said, is exactly what makes Byron Bay the right fit.

“Byron has this fascinating bush-to-beach character,” he said.

“It’s tropical coastline right next to the hinterland. Our product has gone on that journey for decades, but the brand has never really talked about it.”

The company already runs stores in Sydney, Brisbane, Noosa and at its Kempsey workshop, but Byron marks a different direction.

“People are generally looking for a hat when they’re on an adventure,” Fowler said.

“That adventure could be every day, whether you’re a farmer in the hinterland or driving through on holiday.”

Kempsey, on the New South Wales mid-north coast, remains Akubra’s production base.

The workshop there has been operating since 1974.

Rabbit fur arrives in bales and is turned into felt through more than 160 separate steps, cleaned, pressed, shaped and finished by hand.

“It really hasn’t changed much in 150 years,” Fowler said. “That’s the kind of product you’re buying.”

He calls grit and tenacity the words that best describe Akubra’s spirit.

“We’re still doing it the same way we did 150 years ago,” he said. “That single focus on great products has been what’s allowed Akubra to continue successfully.”

At the heart of the business are the company’s Master Hatters, specialists who oversee every stage of production, many of whom have spent decades learning the craft.

Among them are members of the Keir family, who ran the company for five generations before its 2023 sale to Andrew and Nicola Forrest’s private investment group Tattarang.

“It takes deep knowledge, but a hell of a lot of passion,” Fowler said.

“The Keir family still works in the business. They’re passing down generational knowledge not only of the brand but of the craftsmanship behind it.”

Stephen Keir now heads production in Kempsey, while his sister Laura Keir manages learning and development.

“They’re still in it every day,” Fowler said.

“Their dad passed the business to the new team, but the family still work in the company. So if we’re ever talking about the history of a hat or a band, we’ve got a direct line to the people who created them.

That continuity, from nineteenth century workshop to modern retail, is part of what makes it unique.

Fowler, who trained in industrial design, said seeing the process firsthand was “jaw-dropping”.

“You realise how unchanged it all is,” he said. “We literally start from fur and end up with something that can last a lifetime.”

That sense of history extends to the company’s Kempsey shopfront, which sits next to the workshop and still draws travellers on their coastal drives.

“It’s not an overly ornate store, it’s pretty grassroots,” Fowler said. “But that’s what people love about it.”

“It’s close to the Slim Dusty Museum, so you get families stopping in, picking up a hat, and continuing on their way. It’s part of the adventure.”

That same spirit carried into the Byron Bay design brief.

Tucked on the corner of Marvel and Jonson streets near Bayleaf Café and the Mez Club, the new store is a study in coastal restraint.

Inside, the walls are painted a deep kelp green inspired by ocean kelp, the counter is wrapped in cowhide, and two pendant lamps by local designer Coco Reynolds hang over the space.

“We wanted it to feel modern and unassuming,” Fowler said. “Somewhere you can walk in barefoot. It’s no fuss, but rich in texture.”

The colour palette was designed to connect to its environment, the ocean, the bush, and the clay earth beyond the town.

“There’s dashes of country in there,” Fowler said. “It’s literal, but it’s subtle.”

Staff are trained to shape and steam hats on site, a throwback to how hats were once personalised for stockmen and shearers.

“We’ve hired people who have a natural affinity for the product,” Fowler said. “It’s about play. Ask questions, try them on.”

Behind the counter in Byron hangs a photograph of rodeo rider Jed, shot at the Mount Isa Rodeo, feather tucked in his brim and dust on his shirt.

Fowler said the Byron location was chosen deliberately, just outside the busiest retail zone, so the team could take their time with customers.

“We wanted to slow the retail game down,” he said. “Serve people properly. We wanted the store to feel like it could have been here for ten years already.”

Future plans include local collaborations and small touring activations around the Northern Rivers.

The team also hopes to host events and demonstrations, giving visitors a closer look at how each hat is made and shaped.

“We want people to have fun, hang around, play a bit,” Fowler said.

“That’s what matters, a genuine, meaningful connection. A lot of brands have to manufacture their stories, ours is real.”